#Oklahoma Ecology

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Oklahoma Native Plant Network

1 note

·

View note

Text

Conocephalum salebrosum, commonly known as snakewort, is a species of non-vascular land plant in the group of liverworts.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

❤🔥 I want to hear from all of you reading anything!!!

If you see this you’re legally obligated to reblog and tag with the book you’re currently reading

#a very short introduction to adorno - from the very short introduction to series#i heart Oklahoma - Roy Scranton#recovering bookchin a social ecology and the crises of our time - Andy price#theorie van de kraal - Willem schinkel#a lot of philosophy lately#discovering the Frankfurt school really made philosophy sexy#oh yes and also an essay by Carolyn steel#reading

290K notes

·

View notes

Text

my dad gave me a book to read about the Dust Bowl so that, in his words, i would stop missing oklahoma, and jfc is it grim. like i did know it was an environmental catastrophe of almost unimaginable magnitude but all the policies that led up to it are so strikingly and blatantly stupid and also just a blisteringly clear indictment of imperialist and capitalist views of land coming home to roost in spectacularly awful fashion. the way that grasslands were framed as empty desert needing to be civilized through farming - the last gasp of the frontier, and a "make the desert bloom" narrative par excellence - and the urgency of the federal government to get settlers into every conceivable area, and the eagerness of the railroads and land speculators to invent promises to lure people out there, and the delight in the wholesale destruction of an ecosystem and the absolute confidence that people could conquer and remake a landscape as they wished, and that land would forever be an inexhaustible resource... i remember watching the ken burns documentary and being struck by the horror of the dust bowl back then too, but it really needs to be put into context as fallout specifically generated by imperialism and by capitalist & extractivist & white supremacist views of land that were not at all unique to this one catastrophe, and while it was a perfect storm of several terrible courses colliding, it can't be seen as a one-off fluke horror. it's just the extreme end result of the same kinds of reckless rolls of the dice that we're still doing ecologically on a massive scale, with industrial agriculture and with extractivism as a whole

#i don't think 'make me stop missing oklahoma' is quite the outcome here. mostly i just feel grief i think for what was done there#the sense of horror that i had as a kid looking at clear cuts or mountaintop removal or rly any construction site - it's like that#reading abt the willful destruction of an ecosystem and then all the suffering as the sowing was reaped. so to speak#and then thinking abt how much these attitudes and these fucking stupid gambles w how much damage the earth can stand#have actually changed. or not. as the case may be#dust bowl#oklahoma things#skravler

98 notes

·

View notes

Note

The "anti skateboard lattice" is not anti skateboard lattice. It's to help retain water for the surrounding area and prevent loss of top soil. That post is spreading misinformation and its entirely frustrating. I've been to that park. It's in Oklahoma City. Its called Scissortail Park. I know one of the directors and asked him myself.

That park is handicap accessible and this area is only a small area. It's not meant to be a walkway. It's basically for design only

There are normal pathways throughout the rest of the park and there are skate parks in other places in Oklahoma City. That park is actually where they have the Pride Celebration every year as well and last year they had a Dia De Los Muertos festival there and that area is where they put the ofrenda display.

Oh shit, thanks for letting me know! I had to do a small bit of hunting but here's an image which shows more clearly that there's obviously an accessible pathway that is the actual pathway. I'm ngl part of me thinks I should've been able to catch that, but my ecology studies were focused on wilderness settings and not urban design or agricultural stuff, so what can ya do

I'm about to go edit on this photo to that reblog so that misinfo doesn't at least spread when sourced from me. Thanks again!

426 notes

·

View notes

Photo

National Prairie Day

National Prairie Day, on June 3 this year, celebrates the beauty and ecological value of this often-overlooked ecosystem. Spanning more than a dozen American states and several Canadian provinces, the North American prairie is a vast grassland that offers more biodiversity and beauty than most people realize. With their endless, gently rolling plains and highly productive soils, prairies have been a valued location for farming and ranching for thousands of years. Today, only 1% of tallgrass prairie in the United States remains untouched by farming or development. National Prairie Day promotes the appreciation and conservation of America’s native prairies.

History of National Prairie Day

The United States is home to a dazzling array of geographies and environments. Some, like the towering redwoods of California or the majestic cascades of Niagara Falls, enjoy worldwide reputations as media darlings and tourist hotspots. Other ecosystems, like the humble prairie that covers much of the interior United States, receive fewer accolades but play crucially important roles in the development of the nation.

Defined as a flat grassland with a temperate climate and derived from the French for ‘meadow,’ ‘prairie’ has become almost synonymous with the expansion of the American frontier. Flanked by the Great Lakes and the grandiose Rocky Mountains, the North American prairie extends across 15% of the continent’s land area. Other examples of similar grasslands around the world include the pampas in Argentina, the Central Asian steppes, and the llanos of Venezuela.

There’s more to the prairie than meets the eye. In fact, tall grass prairies host the most biodiversity in the Midwest and provide a home for dozens of rare species of animals and plants, including bison, antelope, elk, wolves, and bears.

Native prairies face extinction as more and more land is converted to agricultural and ranching use. Due to its rich, fertile soil, prairie land is prized for agricultural use. Around the world, almost three-quarters of agricultural regions are located in grassland areas. With only 1% of tallgrass prairie in the U.S. remaining untouched, the American tallgrass prairie is now one of the most endangered ecosystems on the planet. The Missouri Prairie Foundation launched National Prairie Day in 2016 to raise awareness and appreciation for the nation’s grasslands. The organization seeks to protect and restore native grasslands by promoting responsible stewardship, supporting acquisition initiatives, and providing public education and outreach.

National Prairie Day timeline

6000 B.C. The Prairie Forms

The North American prairie forms roughly 8,000 years ago when receding glaciers give way to fertile sediment.

1800s The American Prairie Decimated

Throughout the 19th century, farmers and ranchers, excited about the rich potential of prairie soil, convert almost all of the American prairie to farmland and grazing land.

Early 1930s The Dust Bowl

The combination of years of mismanagement, the stock market crash, and drought conditions come to a head as thousands of families in Oklahoma, Texas, and other parts of the Midwest lose everything when their farms fail, driving them to California and elsewhere to seek work in more fertile fields.

2016 First National Prairie Day

The Missouri Prairie Foundation launches the National Prairie Day campaign to promote awareness and conservation of the vanishing ecosystem.

National Prairie Day FAQs

Why don't prairies have any trees?

The environment of the prairie, with its flat terrain, regular droughts, and frequent fires, is uniquely suited to grasses that don’t require a lot of rainfall or deep soil to thrive.

Why are prairies important?

The prairie provides an irreplaceable home for hundreds of plant and animal species, as well as exceedingly fertile soil for human agriculture and ranching. Prairie destruction has had catastrophic effects, like the Dust Bowl that decimated American farms in the 1930s. Prairies also contribute to the conservation of groundwater.

Why did the Dust Bowl happen?

The Dust Bowl disaster that swept the U.S. and Canada in the 1930s had several natural and man-made causes, including severe drought and a failure to properly manage farmland and conserve precious topsoil. A series of intense dust storms wiped out agriculture, eroded the soil, and left the land unable to produce crops.

National Prairie Day Activities

Learn about the prairie

Donate to a conservation group

Plan a visit to a famous prairie

Do a little research to learn about this important American ecosystem and the role it has played in the cultural and economic development of our country.

If you're concerned about the loss of the American prairie, donate to a grasslands conservation group to support their work.

Do you live near a prairie? Try finding the grassland nearest you and plan a visit.

5 Interesting Facts About Prairies

‘Prairie schooners’

Dogtown

Where the buffalo roam

Carbon hero

Rising from the ashes

During the 1800s, when Americans embarked on the long journey westward, their covered wagons were often referred to as ‘prairie schooners.’

Prairie dogs live in vast networks of underground burrows called ‘towns,’ which can cover hundreds of acres and house thousands of prairie dogs with complex social relationships.

When Europeans first arrived in North America, up to 60 million bison roamed the plains — by 1885, there were fewer than 600.

Prairies can help fight climate change — one acre of intact prairie can absorb about one ton of carbon each year.

On the prairie, wildfires can actually be a healthy thing — with more than 75% of their biomass underground, prairie plants are uniquely suited to surviving and thriving after a fire.

Why We Love National Prairie Day

The prairie often gets overlooked

Native grasslands are critically endangered

It reminds us of the diversity of America's ecosystems

It's not often we remember to celebrate grasslands, yet the prairie plays an important role in America's cultural past and environmental future.

With only 1% of America's native prairie remaining, it's more urgent than ever to conserve and protect this vital resource.

The United States has more environmental variety than almost any other country on earth. Celebrating each unique ecosystem reminds us to appreciate and protect all the beauty our country has to offer.

Source

#Colorado#South Dakota#Wyoming#Alberta#Saskatchewan#nature#flora#WickBeumee Wildlife Habitat Management Area#Custer State Park#Rock Springs#Pilot Butte Wild Horse Scenic Loop#Trans-Canada Highway#Texas#landscape#countryside#summer 2022#2019#original photography#wildflower#meadow#first Saturday in June#3 June 2023#National Prairie Day#NationalPrairieDay

60 notes

·

View notes

Note

Land back is literally Nazi 'blood and soil' ideology. The idea that a certain people have a unique connection to the land of a certain region and are the only rightful rulers of it. Every group of 'indigenous' people killed or forced some other group of people off of that land they're on before they took over it. Everyone is a colonizer if you go back far enough. It's totally incoherent.

Posting this publicly so other people can see this too to confirm I'm not just going completely mad. Are y'all seeing this? Did someone really just roll up to my inbox and claim the Land Back movement is comparable to Nazi ideology? Am I making up this clownery?

Anyway, cite your sources. EVERY group is a bold claim. And even then, that doesn't excuse the atrocities committed unto them by the European colonizers, nor the devastation that said colonizers continue to bring upon the planet and Her people.

From an ecological standpoint, stewardship is crucial to many environments. Native humans have tended to the land, and when colonizers "settled" it, they disregarded any care that it may need and, through a mix of killing Natives off and forbidding them from lands they were on first, keept and still keep them from tending it and never bothered learning to tend it themselves. It's the major reason why the Australian wildfires were so devastating.

But we aren't looking at this from a purely ecological standpoint, are we? We're looking at it from a humanitarian perspective, too. When we show up where other people already are and violently remove them from where they've lived for countless generations, make them houseless, starve them, defile their sacred spaces, mass murder their main sources of food and fabric, forcibly convert them to our religions, separate them from their families, and punish them for speaking their own languages... is it right? Does the fact that some of these nations have warred with others in the past make this okay? Does that make this treatment justified? (I'd think this is a rhetorical question, but considering this anon showed up I feel the need to specify: the answer is OBVIOUSLY NOT.)

This is just the list that I, a white man in the US, came up with on the spot, and this is only about a few of the abuses committed by the US alone. There's a lot more to be added here. No people deserve such mistreatment and no people ever will.

The continued persecution of Native peoples around the world will not end until the rights to stewardship of lands they had stolen from them are acknowledged.

LAND BACK NOW

Edit: Whenever I come back to edit this, Tumblr deletes all my sources in that big block of atrocities, so I'm just posting them all here below. TW for racism, genocide, and...just about everything else.

#land back#landback#nativeamericans#us politics#australian politics#hawaiian politics#native rights#indigenous australians#aboriginal australian#aboriginal rights#indigenous rights#politics#fought tumblr putting all those links in#the absolute clownery#racism#I can't keep editing the mistakes in this because Tumblr keeps destroying all the links in the middle paragraph 😒#this is why it took hours to type#genocide

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

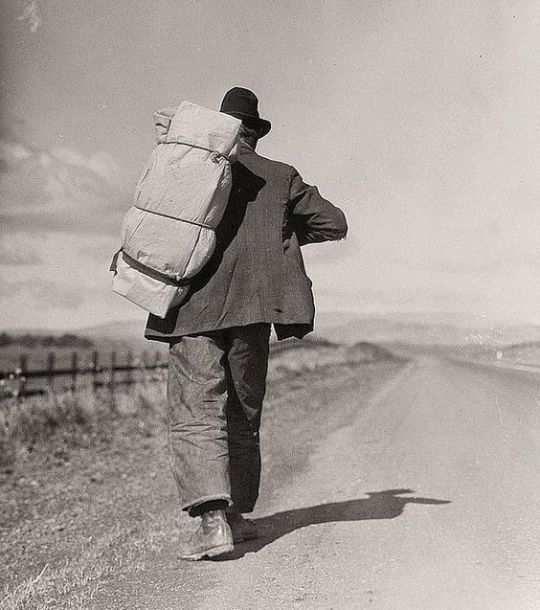

History of the American Dust Bowl

The series of intense dust storms, starting in 1930 and affecting the southern plains of the United States, has been called the greatest ecological disaster ever to happen on American soil. Over the next decade, tens-of-thousands of people were forced to leave their homes under apocalyptic conditions: rolling storms that blocked out the sun, wind laced with particles sharp enough to blind, dust filling up and choking the lungs of the young and old.

Starting with the trade embargo on Russia during World War I, the value of wheat in America and around the world sky-rocketed. The US Government made offers, real estate agents made promises, and an unusual wet season strengthened conviction: come to the prairie, grow wheat for our soldiers – there’s money to be made.

As large-scale farming expanded on the Prairies, inexperienced farmers or “sodbusters” replaced indigenous grasses with wheat crops. In less than ten years, over one hundred million acres of prairie land – overused by mechanized equipment and exacerbated by a severe drought – lost its topsoil and became an instant target for wind erosion. The country’s financial bedrock had been bled dry and now the land had been wrung out too.

In April 1935, on a day that became known as Black Sunday, around 4PM, a rapidly moving “black blizzard” hit Kansas. High winds at 100 miles an hour reportedly displaced 300,000 tons of topsoil. The rolling cloud was over 1,000 miles long, and covered 800 miles by the time it dissipated. Drivers were forced to take refuge in their cars, while other residents hunkered down in basements, barns, fire stations and tornado shelters, as well as under beds.

Folksinger Woody Guthrie, then 22, who sat out the storm at his Pampa, Texas home, recalled that “you couldn’t see your hand before your face.” Inspired by proclamations from some of his companions that the end of the world was at hand, he composed a song titled “So Long, It’s Been Good to Know Yuh.” Guthrie would also write other tunes about Black Sunday, including “Dust Storm Disaster.”

This was by far the worst storm suffered by those in the southern plains (an area reaching from the north of Texas, up the Dakotas and out to Kansas and Oklahoma), and as a result 17 people died, and three suffocated from the dirty wind. As a direct result of American greed and disregard for the natural world, the very skin of the Earth had been ripped up, leaving behind loose, dry soil – abandoned with no concern for conservation and regrowth. All of this, on top of a financial downturn that left over three millions of Americans without jobs, a home, or income.

For many, the Dust Bowl was the closest they ever got to the end of the world, nature’s apocalypse. Much of the Red Cross relief and FDR’s conservation efforts were focused on regrowing that topsoil and putting thousands of out-of-work farmers back on the land. By working in harmony with the land, the southern prairie was rebuilt, the dust storms died down, and the economy righted itself in the face of a new world war.

Apocalypse averted.

In 2023, global weather conditions are changing again due to man-made intervention and ecological carelessness. Year after year, heat records are broken and droughts last longer and longer. The earth is adapting to fit rising temperatures and expanding greenhouse gasses. It is evolving, much like a fungus, to meet its needs in a new climate.

Hopefully, this fic feels as foreign as an AU can, but as familiar as the show’s concern for global warming. There are no blind, clicking zombies in this fic, but there are monsters.

There are always monsters at the end of the world.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’ve tried to write this post like 50 times but couldn’t really get anything to come out right. So just gonna try to be concise here:

Used to grow up in a heavily wooded area. Used to think prairies were boring and like … areas devoid of trees were obviously ecological wastelands in need of rehabilitation.

Moved to Oklahoma … then South Dakota (brief interlude in Nevada but that’s not related to my point).

No longer think prairies are boring and really actually I like them. Turns out prairies aren’t vast, flat wasteland. Turns out they’re like full of life and if you’ve been anywhere in western South Dakota (or portions of western Oklahoma for that matter) … you realize prairies can be flat but like … not always. Also bison are very cute when viewed from a safe distance and they’re not in a huge heard licking the salt off of your car.

So prairies good actually. Prairies really good.

Bison tax:

Seriously don’t drive through Custer State Park’s wildlife loop in the winter/early spring unless you’re ready for your car to get a free cleaning and you to get 10 years taken off of your life.

#look I’m coming off of a night shift and I’m only partially coherent#this is the best you’re getting from me

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello person I don't know at all! I've had this oc that is a world hopping ecology student but the problem is, I don't know what ecology students actually do. The internet is being very vague. Please tell me your experiences.

The world hopping part doesn't matter, it's a side thing but their a college student first and foremost. Also, what do you usually wear when your out in the field? Thanks for humoring me if you answer this.

I got this question asked to me like.... nine months ago, and I just never answered it.

Unfortunately, I never answered it because there really isn't an answer (and also I was in the middle of school and it was thrashing me). Ecology is a big field, usually loosely connected by a couple different traits. (Unfortunately, outfit isn't one of them). Google isn't helping you because that's a very vague question.

I work in grasslands in the South (Arkansas, Oklahoma, those kinds of places). If I wore the same clothes as my lab mate who worked on fish (rubber waders), I would be sad (and uncomfortable. and very sweaty). If I wore the same clothes as my classmates who work in Alaska, I would die of heat exhaustion.

World hopping is unfortunately not a super common trait for an ecologist. It definitely happens (I went to a really cool talk from one like two years ago; she does surveys with the native people of various regions about what plants they use for traditional medicines, and what they do to prepare them, and then looks to see what/how these medicines help at the molecular level) but usually (especially by grad school) you find a niche and really stick to it. I'd be virtually useless in the tundra or the Amazon rainforest, because... I work in grasslands. Not that you couldn't figure it out but there would be a ton of learning to do.

Ecologists generally end up very specialized. I personally work on assessing ecosystem metrics and land use factors to see how it affects biodiversity in fragmented regions. Another person I knew did fish disease modelling. I saw a talk on genome sequencing mussels.

Not to be the guy that says "you need to do more research", but if your character is doing research and that's a major proponent of the story, you're going to need to understand ecological research better and pick more of a specialty than just saying "ecologist".

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Circling the drain in Twisters

In an interview with CNN, director Lee Isaac Chung is quoted as saying, "I wanted to make sure that we are never creating a feeling that we're preaching a message, because that's certainly not what I think cinema should be about. I think it should be a reflection of the world." If this is the case, then Lee Isaac Chung is clearly an idiot, because his studious commitment to avoiding anything that could be construed as an ideological statement has seen him create a world where tornadoes are wild beasts—something like a tiger, or a hippopotamus, maybe—which roam the American plains and will hunt you for sport, as opposed to a mindless confluence of meteorological factors. Says one of the characters: "We're having a once-in-a-generation tornado outbreak in Oklahoma. […] It's getting worse every year." An "outbreak", as if this is some freak disaster, a sudden pandemic of unclear origins, and not a predictable trend where each year is the worst year on record. Don't think of it as a microcosm for the meteorological hardships happening all over the world, year after year—think of it more like 30-50 feral hogs, a consistent but localised problem, the kind of thing you can solve by climbing into the back of your pickup truck with an AR-15.

Certainly, it can't have anything to do with climate change, two words which—despite scriptwriter Mark L. Smith's assurance that the film would "shine a light on […] the causes and effects of climate change"—go completely unmentioned in the entire 122 minute runtime of this dumpster fire.

Pass through the eye of the "Keep reading" button below to see the rest of my blustering.

I know that everyone is sick of ecological stories. I know that, if we're being bluntly honest, all the movies and books and comics and thinkpieces in the world don't mean a fucking thing to the blood-soaked oil industry or our ghoulish politicians. I can understand the instinct to flinch away from the aesop. But to put it as simply as I can: there is no way to neutrally talk about the weather. To even try is to fail, because you end up coming off like a climate denialist.

Oh yeah, this film is also dogshit on pretty much every other level you can conceive of. From the opening prologue, which introduces protagonist Kate's hi-and-die friends, the film is constantly two steps behind the audience, as it clumsily plays out the most paint-by-numbers plotting you can predict in your sleep. You know these people are going to die, you can divine the fucking order they'll be killed off in. And still, on a pure spectacle level, this prologue is about as exciting as the film will ever manage to be; every subsequent bit of tornado action is just a bloodless encore, devoid of stakes or novelty, just CGI nonsense completely divorced from any kind of spatial grounding (in one scene, an oil refinery sort of just appears from nowhere so that the tornado can blow it up).

The film's main conflict is between a team of meteorologists led by Kate's old friend Javi, and a crew of redneck storm-chasers led by a YouTuber "tornado wrangler", Tyler. While I wouldn't say that these groups are overtly representatives of "science" and "gut feeling" respectively—because again, Lee Isaac Chung is a spineless filmmaker who clearly wouldn't know substance if he ate a brownie laced with it—their differing approaches to storm-chasing are contrasted throughout the film. To begin with, we're led to trust Javi's team because of his existing rapport with Kate, their professionalism and preparation, their apparently noble goals, and their class status as white-collar engineer-types. Meanwhile, Tyler's gang are initially presented as stupid, reckless, dangerous, opportunistic, money-motivated, and backwards.

But then, aha, here comes the movie's one (1) twist! (And here I thought the whole titular basis of the movie was that there'd be multiple.) It turns out that actually the rednecks have only been selling all those T-shirts to charitably fund disaster relief, food for the victims of tornadoes. Actually, YouTuber Tyler is a really good storm chaser, and he's also quite caring, and also hot. Meanwhile, the scientists are actually in the pockets of land baron Marshall Rigg, who's profiteering from the tornados by buying victims' property from them for rock-bottom prices in the wake of devastation. For a moment, it actually seems as if Marshall Rigg is some kind of MCU supervillain with an evil master plan to create his own tornadoes and take over the entire USA—because that's the kind of level of reality this film is operating on. If this truly is a "reflection of the world", as Chung claims, then it's a funhouse mirror- no, a flimsy plastic compress, free with a girls' magazine, a paper sticker inside, printed with the face of a beautiful cowgirl.

This "what if the bad guys… were good!" twist isn't really a reveal, so much as it is the script turning these people into completely different characters. They start out as cardboard-cutout trailer-trash, hooting and grinning, and then they are substituted out for an entirely different set of cardboard cutouts, doe-eyed.

The character writing in this film is absolutely embarrassing. In one scene, Kate and Tyler end up at a motel when the tornado sirens start going off. The other people at the motel, ignoring this, continue complaining to the receptionist. "Nine times out of ten, it's a false alarm," one of them says. The power goes out, causing the siren to stop. "You hear that? No tornado." Another anonymous alien says to the receptionist, "Hey, I don't want to give you a bad review." Then a tornado rips the roof off the place. They run outside. The first person is yelling, "There's a tornado! There's a tornado!" Then gets sucked up and killed. Look, nevermind the mean-spiritedness of it, nevermind the misanthropy—what sane writer would ever think that real people would actually behave this way? The script is constantly tripping over itself to make sure you get the jokes; here, the joke is that the woman thought there wasn't a tornado, but then she realised that actually there was.

I recall another example from earlier in the film: when Kate and Tyler are still competing, two tornadoes appear, and the rival storm chasers wind up splitting up, each going after a different one. Just as it seems like Tyler is coming up into the eye of his storm—suddenly, the whole thing dissipates, as though it was never there. They get out of the vehicle, and he looks over the horizon, where Kate's tornado is still swirling. And Tyler's pal says, "We should've went with her." Buddy, I am watching the fucking screen! You can see it right on his face that he should've went with her, you don't need to have one of your characters blurt it aloud. Are you scared I've fallen asleep in the ten seconds since someone last spoke?

God, I haven't even talked about the romance yet! Throughout the movie, YouTuber Tyler keeps popping up around Kate, and you can tell the filmmakers really don't want you to think about the fact that this plotting contrivance basically just implies he's stalking her everywhere. Kate reveals herself to be a country girl at heart. Tyler reveals himself to know about science and stuff, through dialogue where he reels off complicated jargon which you figure probably isn't accurate, or if it is, is the kind of basic meteorology the scriptwriter could piece together by poking around on Wikipedia for a couple of hours. The film doesn't actually give a fuck about science, or the scientific method, or meteorology, because in this movie science is a glossy CGI simulation of a twister which our heroes plug numbers into until the whole thing flashes green or whatever. It's telling, I think, that the onscreen simulation and the CGI twisters themselves are no different from one another—it's all artifice, isn't it, intangible particle effects swirling around, signifying nothing.

People seem to be going mad over Glen Powell in this thing, but come on, are you really satisfied by this sexless nothingburger of a romance? They don't even fucking kiss, right? All blockbusters are like this. I'm starving. This film can't even be bothered to crystallise a proper love triangle between Javi, Kate, and Tyler, even though you can tell it's thinking about it. It's as if the film itself knows it wouldn't even be compelling if it tried. Considering the absolutely abominable emotional manipulation Javi uses to get Kate onboard with the project—which the film never seems to quite become cognizant of—it's for the best anyway. "Hey, remember how your boyfriend and your best friends all died right in front of you? Well if you don't come help me by putting yourself in that exact same situation again, loads more people are going to die like that too!" Unhinged. Put that man in the twister, and the filmmakers too.

So yeah, I think I hate this flick. It's a movie that exists to soothe the conscience of its audience: see, we don't really hate the South, it's not our fault the planet is trying to blast us off the face of it, we're all trying our best. Let's watch a rodeo or something. It's the kind of film that can lull you to sleep, like a final, fatal injection.

Rating: 2/10

If you’ve enjoyed this review, you can find dozens of similar essays over on my Letterboxd account.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Oklahoma Native Plant Society

0 notes

Text

Indigenous territories and protected areas are key to forest conservation in the Brazilian Amazon, study shows

https://sciencespies.com/nature/indigenous-territories-and-protected-areas-are-key-to-forest-conservation-in-the-brazilian-amazon-study-shows/

Indigenous territories and protected areas are key to forest conservation in the Brazilian Amazon, study shows

A research study led by researchers with the Center for Earth Observation and Modeling at the University of Oklahoma analyzed time series satellite images from 2000 to 2021, revealing the vital role of Indigenous territories and protected areas in forest conservation in the Brazilian Amazon. The study results, recently published in Nature Sustainability, called attention to the negative impacts of weakened governmental conservation policies in recent years.

The Brazilian Amazon encompasses the largest tropical forest area with the highest biodiversity in the world. Since 2000, Indigenous territories and protected areas have increased substantially in the region and by 2013, Indigenous territories and protected areas accounted for 43% of the total land area and covered approximately 50% of the total forest area.

However, tensions between forest conservation and socioeconomic development goals persist. In recent years, forest conservation has been threatened by large socio-ecological changes in Brazil. Weakened forest and environmental policies and enforcement as well as impacts from the COVID-19 pandemic had devastating impacts on Indigenous groups in the region.

In this U.S.-Brazil collaborative study, Yuanwei Qin, Ph.D., and Xiangming Xiao, Ph.D., of OU’s Center for Earth Observation and Modeling, with Fabio de Sa e Silva, Ph.D., assistant professor of international studies and Wick Cary Professor of Brazilian Studies in the OU College of International Studies, worked with collaborators from the Brazilian National Institute for Space Research and the National Institute for Research in Amazonia in Brazil. The research team combined multiple data sources to document and quantify the dynamics and impact of forest loss in the Brazilian Amazon over the past two decades.

Because of frequent cloud cover and fire-induced smoke in the Brazilian Amazon, annual forest maps from analyses of optical images have only moderate accuracy. In a 2019 paper published by the same journal, the research team combined image data from both optical and microwave sensors to generate annual Brazilian Amazon forest maps. Using these annual forest maps, they assessed the effects of Indigenous territories and protected areas on deforestation dynamics in the Brazilian Amazon through 2021.

“Between 2000 and 2021, the areas designated as Indigenous territories or protected areas increased to cover approximately 52% of forests in the Brazilian Amazon, accounting for only 5% of net forest loss and 12% of gross forest loss in the period,” said Qin. “This finding highlights the vital role of Indigenous territories and the protected areas for forest conservation in the region.”

The protected areas in the Brazilian Amazon are subject to different state and national governance arrangements and have different management objectives, including strict protection or sustainable use. They found that from 2003 through 2021, gross forest loss fell 48% in the protected areas subject to strict protection and 11% in the protected areas subject to sustainable use.

“These varying effects on forest conservation call for more in-depth causal analyses by researchers and invite stakeholders, decision-makers, and the public to reassess existing policies for these areas. Legal designations are important, but if the law is not enforced, the intended protection of forests and biodiversity will be illusional. This is an area in which Brazil is knowingly failing,” de Sa e Silva said.

The results from this study also show that annual forest area loss was affected by Brazilian forest policies, as evidenced by a large reduction of forest area loss in the early 2000s to mid-2010s, corresponding with Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva administration in 2003-2010, and renewed rise of forest area loss even among Indigenous territories and the protected areas in 2019-2021, corresponding with President Jair Bolsonaro’s administration in 2019-2022.

“How to rebuild effective policies and reduce forest area loss in the Brazilian Amazon in the coming years will be one of the grand challenges for Lula’s administration and international communities,” Xiao said.

This study adds to a portfolio of research efforts to document forest areas in the Brazilian Amazon by Qin and Xiao, including a 2019 paper, “Improved estimates of forest cover and loss in the Brazilian Amazon in 2000-2017,” published in Nature Sustainability; a 2021 paper, “Carbon loss from forest degradation exceeds that from deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon,” published in Nature Climate Change; as well as two others.

Story Source:

Materials provided by University of Oklahoma. Original written by Chelsea Julian. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

#Nature

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another wonderful book about Indigenous ecology is Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer. She's Potawatomi so her ancestral land is in the Great Lakes region and her reservation land is in Oklahoma.

What I was taught growing up: Wild edible plants and animals were just so naturally abundant that the indigenous people of my area, namely western Washington state, didn't have to develop agriculture and could just easily forage/hunt for all their needs.

The first pebble in what would become a landslide: Native peoples practiced intentional fire, which kept the trees from growing over the camas praire.

The next: PNW native peoples intentionally planted and cultivated forest gardens, and we can still see the increase in biodiversity where these gardens were today.

The next: We have an oak prairie savanna ecosystem that was intentionally maintained via intentional fire (which they were banned from doing for like, 100 years and we're just now starting to do again), and this ecosystem is disappearing as Douglas firs spread, invasive species take over, and land is turned into European-style agricultural systems.

The Land Slide: Actually, the native peoples had a complex agricultural and food processing system that allowed them to meet all their needs throughout the year, including storing food for the long, wet, dark winter. They collected a wide variety of plant foods (along with the salmon, deer, and other animals they hunted), from seaweeds to roots to berries, and they also managed these food systems via not only burning, but pruning, weeding, planting, digging/tilling, selectively harvesting root crops so that smaller ones were left behind to grow and the biggest were left to reseed, and careful harvesting at particular times for each species that both ensured their perennial (!) crops would continue thriving and that harvest occurred at the best time for the best quality food. American settlers were willfully ignorant of the complex agricultural system, because being thus allowed them to claim the land wasn't being used. Native peoples were actively managing the ecosystem to produce their food, in a sustainable manner that increased biodiversity, thus benefiting not only themselves but other species as well.

So that's cool. If you want to read more, I suggest "Ancient Pathways, Ancestral Knowledge: Ethnobotany and Ecological Wisdom of Indigenous Peoples of Northwestern North America" by Nancy J. Turner

55K notes

·

View notes

Text

National Prairie Day

National Prairie Day, on June 1 this year, celebrates the beauty and ecological value of this often-overlooked ecosystem. Spanning more than a dozen American states and several Canadian provinces, the North American prairie is a vast grassland that offers more biodiversity and beauty than most people realize. With their endless, gently rolling plains and highly productive soils, prairies have been a valued location for farming and ranching for thousands of years. Today, only 1% of tallgrass prairie in the United States remains untouched by farming or development. National Prairie Day promotes the appreciation and conservation of America’s native prairies.

History of National Prairie Day

The United States is home to a dazzling array of geographies and environments. Some, like the towering redwoods of California or the majestic cascades of Niagara Falls, enjoy worldwide reputations as media darlings and tourist hotspots. Other ecosystems, like the humble prairie that covers much of the interior United States, receive fewer accolades but play crucially important roles in the development of the nation.

Defined as a flat grassland with a temperate climate and derived from the French for ‘meadow,’ ‘prairie’ has become almost synonymous with the expansion of the American frontier. Flanked by the Great Lakes and the grandiose Rocky Mountains, the North American prairie extends across 15% of the continent’s land area. Other examples of similar grasslands around the world include the pampas in Argentina, the Central Asian steppes, and the llanos of Venezuela.

There’s more to the prairie than meets the eye. In fact, tall grass prairies host the most biodiversity in the Midwest and provide a home for dozens of rare species of animals and plants, including bison, antelope, elk, wolves, and bears.

Native prairies face extinction as more and more land is converted to agricultural and ranching use. Due to its rich, fertile soil, prairie land is prized for agricultural use. Around the world, almost three-quarters of agricultural regions are located in grassland areas. With only 1% of tallgrass prairie in the U.S. remaining untouched, the American tallgrass prairie is now one of the most endangered ecosystems on the planet. The Missouri Prairie Foundation launched National Prairie Day in 2016 to raise awareness and appreciation for the nation’s grasslands. The organization seeks to protect and restore native grasslands by promoting responsible stewardship, supporting acquisition initiatives, and providing public education and outreach.

National Prairie Day timeline

6000 B.C. The Prairie Forms

The North American prairie forms roughly 8,000 years ago when receding glaciers give way to fertile sediment.

1800s The American Prairie Decimated

Throughout the 19th century, farmers and ranchers, excited about the rich potential of prairie soil, convert almost all of the American prairie to farmland and grazing land.

Early 1930s The Dust Bowl

The combination of years of mismanagement, the stock market crash, and drought conditions come to a head as thousands of families in Oklahoma, Texas, and other parts of the Midwest lose everything when their farms fail, driving them to California and elsewhere to seek work in more fertile fields.

2016 First National Prairie Day

The Missouri Prairie Foundation launches the National Prairie Day campaign to promote awareness and conservation of the vanishing ecosystem.

National Prairie Day Activities

Learn about the prairie

Donate to a conservation group

Plan a visit to a famous prairie

Do a little research to learn about this important American ecosystem and the role it has played in the cultural and economic development of our country.

If you're concerned about the loss of the American prairie, donate to a grasslands conservation group to support their work.

Do you live near a prairie? Try finding the grassland nearest you and plan a visit.

5 Interesting Facts About Prairies

‘Prairie schooners’

Dogtown

Where the buffalo roam

Carbon hero

Rising from the ashes

During the 1800s, when Americans embarked on the long journey westward, their covered wagons were often referred to as ‘prairie schooners.’

Prairie dogs live in vast networks of underground burrows called ‘towns,’ which can cover hundreds of acres and house thousands of prairie dogs with complex social relationships.

When Europeans first arrived in North America, up to 60 million bison roamed the plains — by 1885, there were fewer than 600.

Prairies can help fight climate change — one acre of intact prairie can absorb about one ton of carbon each year.

On the prairie, wildfires can actually be a healthy thing — with more than 75% of their biomass underground, prairie plants are uniquely suited to surviving and thriving after a fire.

Why We Love National Prairie Day

The prairie often gets overlooked

Native grasslands are critically endangered

It reminds us of the diversity of America's ecosystems

It's not often we remember to celebrate grasslands, yet the prairie plays an important role in America's cultural past and environmental future.

With only 1% of America's native prairie remaining, it's more urgent than ever to conserve and protect this vital resource.

The United States has more environmental variety than almost any other country on earth. Celebrating each unique ecosystem reminds us to appreciate and protect all the beauty our country has to offer.

Source

#Alberta#big sky country#Custer State Park#I love Custer State Park#flora#nature#meadow#original photography#landscape#countryide#vacation#travel#summer 2019#South Dakota#Trans-Canada Highway#Wyoming#Nevada#I'll be back this summer#USA#National Prairie Day#NationalPrairieDay#first Saturday in June#1 June 2024#White Mountain#Nebraska#Oglala National Grassland#Saskatchewan#Texas#landmark#tourist attraction

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Work by Adrienne Elise Tarver

Work by Ray Anthony Barrett

Work by Cara Despain

Work by Andrae Green

One room with sculpture by Margaret Griffith

Against Dystopia, the group exhibition at Diane Rosenstein curated by niko w. okuro, presents a variety of interesting work that speaks to the times we are living in.

The exhibition includes ten international artists representing twelve cities across the United Kingdom, Jamaica, and all five regions of the United States- Ray Anthony Barrett, Ashanti Chaplin, Phoebe Collings-James, Cara Despain, Andrae Green, Margaret Griffith, Jane Chang Mi, Olivia “LIT LIV” Morgan, Esteban Ramón Pérez, and Adrienne Elise Tarver.

From the gallery-

Presented on the eve of the 2024 presidential election, Against Dystopia is ‘a far-reaching exhibition, both in terms of the diverse backgrounds and approaches of its featured artists, and the social, cultural, and geographic ecosystems those artists represent and critique,’ writes okoro, who is based in New Haven, CT. The exhibition ‘features artworks that inhabit a spectrum of anti-dystopian thought, from mobilizing conceptualism to overcome historic traumas and the precarity of the present, to envisioning future utopias against seemingly insurmountable odds.’

Against Dystopia transforms fear and anxiety surrounding the uncertainty of our shared future into a tangible site of hope—one where collective memory reminds us of our agency to enact change today, and rich cultural traditions empower us to imagine alternative futures. Of significance is the inclusion of artists who identify as multi hyphenates, playing numerous social roles within their communities, such as advocate, change agent, chef, documentarian, educator, father, filmmaker, mother, musician, oceanographer, researcher, and too many more to name.

Artworks are grouped into three thematic sections, each of which explores creative strategies of resistance and works against dystopia at all costs: field research, symbolic interactionism, and speculative fiction.

Ray Anthony Barrett (Missouri), Ashanti Chaplin (Oklahoma), Cara Despain (Utah/Florida), and Jane Chang Mi (Hawai‘i/California) use field research to map histories of frontierism, settler colonialism, and land politics onto ecological and socioeconomic systems today. With a focus on listening to the land and sea to both unearth and atone for difficult truths, these artists name and dismantle dystopian practices on the path to reconciliation. Embracing an appreciation for both hyperlocal traditions and the tenets of global citizenship, each underscores our shared duty to ensuring ecocultural sustainability and Earth’s habitability for future generations.

While Margaret Griffith (California), Olivia Morgan (New York), and Adrienne Elise Tarver (New York) work through markedly different mediums and styles, they share a fearlessness in addressing ongoing tensions and questions surfaced amidst the political firestorm of 2020. Embracing tenets of symbolic interactionism, or the theory that individuals shape and are shaped by society through daily interactions and the co-creation of meaning from symbols, these artists remind us of the power of human connection to bridge difference. Each steers towards social cohesion by processing collective grief and the enduring impacts of the 2020 presidential election, the proliferation of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter Movement respectively. Whereas Morgan and Griffith subvert symbols that often polarize rather than unite us within physical space—such as fences, face masks, and smartphones—Tarver reaches into the past to pull forth reimagined symbols that speak to our spiritual interdependence.

Phoebe Colling-James (United Kingdom), Andrae Green (Massachusetts/Jamaica) and Esteban Ramón Pérez (California) boldly envision alternative realities by using speculative fiction and symbolic allegory to sew threads of connection across time and space. Each resists linearity and subverts narrative tropes to instead materialize the fluid spiritual dimensions of lived experience. Through their layered ceramics, paintings, and sculptures, these artists mine the depths of their respective Jamaican/British, Jamaican/American, and Chicanx heritages to comment more broadly on social conditions today, prompting us to dream beyond what’s readily visible or knowable.

Against Dystopia opens concurrently with The Getty’s Pacific Standard Time: Art x Science x LA, which similarly explores, “opportunities for civic dialogue around some of the most urgent problems of our time by exploring past and present connections between art and science.” By convening an international group of visionary artists to help initiate these dialogues, Against Dystopia prompts viewers to pursue deeper understanding of shared challenges and solutions, on both the micro and macro levels.’

Below are a few more selections-

Photos by Olivia "LIT LIV" Morgan

Installation by Ashanti Chaplin

Work by Jane Chang Mi

Paintings by Andrae Green and sculpture by Phoebe Collings-James

Work by Margaret Griffith

This exhibition closes 11/2/24.

#Diane Rosenstein Gallery#Los Angeles Art Shows#Diane Rosenstein#niko w. okuro#Adrienne Elise Tarver#Andrae Green#Art#Art Installation#Art Show#Art Shows#Ashanti Chaplin#Cara Despain#Drawing#Esteban Ramón Pérez#Fiber Art#Fiber Arts#Jane Chang Mi#Los Angeles Art Show#Margaret Griffith#Olivia “LIT LIV” Morgan#Painting#Phoebe Collings-James#Photography#Printmaking#Ray Anthony Barrett#Sculpture#Weaving

1 note

·

View note